JPEG

The Photographer. Great for compressing real-world photos. It “throws away” invisible details to save space (lossy).

To a computer, an image isn’t a photograph or a painting—it’s just a grid of numbers.

Understanding this numeric structure is the secret weapon of computer vision. Once you stop seeing “pictures” and start seeing “matrices,” operations like edge detection, color filtering, and object recognition become simply math problems.

Imagine zooming into a photo until it turns into a blocky mosaic. Each of those blocks is a pixel (Picture Element), the fundamental atom of a digital image.

(y, x) or (row, col). This is slightly counter-intuitive if you’re used to Cartesian (x, y) coordinates, but standard for matrices.When you load an image in OpenCV, you aren’t getting a special “Image Object”—you’re getting a NumPy array.

This is one of OpenCV’s most powerful design choices. By using standard NumPy arrays, OpenCV images are compatible with the entire Python scientific ecosystem (like Matplotlib, Scikit-learn, and Pandas) right out of the box. You don’t need special converters; if you know how to work with data lists in Python, you already know how to edit images.

A black-and-white (grayscale) image is the simplest form. It’s a 2D matrix (think of an Excel sheet) where each cell represents a single pixel’s intensity.

Computer vision algorithms often convert color images to grayscale first. Why? Because for tasks like detecting edges or reading text, you only care about light intensity shapes, not color. Dropping color reduces the data by 66%, making your code run significantly faster.

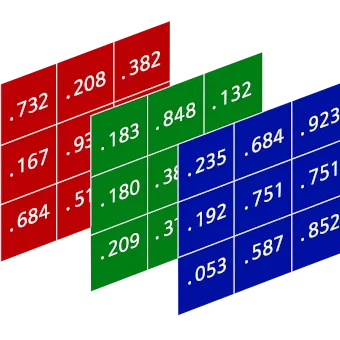

Image Matrix (8-bit grayscale), 3x3 pixels:┌─────────────────┐│ 0 128 255 │ <- Row 0 (Black -> Gray -> White)│ 255 128 0 │ <- Row 1 (White -> Gray -> Black)│ 50 50 50 │ <- Row 2 (Dark Gray line)└─────────────────┘Color images add a third dimension. Instead of a single sheet of numbers, imagine three sheets stacked on top of each other. Each sheet represents a color channel: typically Blue, Green, and Red.

So, a single pixel isn’t just one number—it’s a vector of three numbers (B, G, R).

[255, 0, 0] (Max Blue, No Green, No Red)[0, 0, 255] (No Blue, No Green, Max Red)[255, 255, 255] (Max of all colors)[0, 0, 0] (No light at all)This structure (Height, Width, Channels) is why you’ll see shapes like (1080, 1920, 3).

Here is how this looks in actual Python code. Notice that “loading an image” is really just “loading a matrix from a file.”

import cv2import numpy as np

# Load an imageimg = cv2.imread('photo.jpg')

# 1. CHECK THE SHAPE# .shape gives (Rows/Height, Columns/Width, Channels)# If it returns (500, 500), it's grayscale (no channels dimension).# If it returns (500, 500, 3), it's a color image.print(f"Shape: {img.shape}")

# 2. READ A PIXEL# Let's look at the pixel at Row 50, Column 100px = img[50, 100]print(f"Pixel value at (50, 100): {px}")# Output: [240 50 50] -> Roughly equivalent to Blue=240, Green=50, Red=50

# 3. MODIFY A PIXEL# Change that pixel to pure Blueimg[50, 100] = [255, 0, 0] # [Blue, Green, Red]Since images are just arrays, we don’t need to load a file to have an image. We can create one mathematically using np.zeros() (which creates a matrix filled with 0s).

Why 0s? Because 0 is black. So np.zeros() effectively creates a black canvas.

# 1. Create a black canvas# Dimensions: 480px tall, 640px wide, 3 channels (Color)# dtype=np.uint8: CRITICAL! Images expect 8-bit integers (0-255).# If you use floats, OpenCV might get confused.canvas = np.zeros((480, 640, 3), dtype=np.uint8)

# 2. Draw a Blue line across the middle# Set Row 240, All Columns (:), Channel 0 (Blue) to 255canvas[240, :, 0] = 255You’ll noticed we keep mentioning “0 to 255.” Why that specific range?

It comes down to memory efficiency. A standard image uses 8 bits (1 byte) to store each color value.

You’ll encounter different wrappers for this data.

JPEG

The Photographer. Great for compressing real-world photos. It “throws away” invisible details to save space (lossy).

PNG

The Artist. Preserves every single pixel value exactly (lossless). Supports transparency. Great for screenshots and diagrams.

TIFF

The Archivist. Heavy, professional, often uncompressed. Used when quality matters more than disk space.

WebP

The Modernist. A newer format that often beats JPEG and PNG at their own game. Efficient for web.

Understanding this structure explains why:

(Row, Col) vs Cartesian (x, y).Now that you know the matrix, you’re ready to start manipulating it.